Copyright © 2011-2012 Opus 9 Media LLC. www.opus9media.com. info@opus9media.com.

COLUMN: Sound Board

Angst and Worship at the Opera

By Ilona Goin

3

3

Back a bit late from intermission one evening, and not quite finished with my rare treat of chocolate from the opera salon, I made the serious mistake of crinkling the plastic wrapper during a particularly pianissimo section. While I knew the conductor was a very agile man, I had no idea that he could turn so fast, nor that a person could stare so hard. I froze in my seat. And I never again ate another piece of anything during a performance within the hallowed hall of The Norwegian Opera. Not even in later years, when I preferred the view from the lofty perch of the balcony and was well out of earshot.

It was a matter of respect, not only for the conductor but for the magnificent composition, and for the wonder of music itself. By then a music student, I understood what a privilege it was to enjoy good music. And I knew that, as a practicing musician who was literate in the language of music, it was my responsibility to protect the sacredness of what took place in a concert hall.

For the musician, the concert hall is as good as a holy place, a temple of worship, and the act of performing is a spiritual ritual. To be a singer is to open mind and heart to grace and sing God’s praises, whatever the words. To partake of divinely inspired music is a form of communion through which the spirit of God uplifts the soul and grants it wings and wisdom. Thus, to sing or play music is at once a gift received and an act of service, and both are to be honored. That is why the purest music—be it at the opera, in the Ozarks, in a club, or in church—originates in a state of gratitude and the joy of living.

Copyright © 2011-2012 Ilona Goin. All rights reserved.

The orchestra seemed a masterpiece of sound and movement, intent and interpretation, divine inspiration and sometimes imperfect imagination. It was a detailed design carefully brought to life by the conductor and his talented team. I watched the violin bows in a furious vertical dance; excited bobbing flutes; and French horns occasionally rising from their comfortable position on laps for a few bars as mellow and warm as a summer sunset. Able to see the musicians at work, I had a visual display of the score. By watching as well as listening, I learned about the temperaments, ranges, and uses of the various instruments. These performances were my first lessons in orchestration.

This early education gave me an understanding of the sometimes playful, sometimes competitive, relationship between the orchestra and the soloists. The two would work off each other in a concerto grosso mode in one section, while in the next, the instruments would gracefully support and submit to the voices. I marveled at the skill with which the composers blended orchestra, choir, and soloists to build a world that reached far beyond the stage.

It is at the opera that I fell in love with the sweet, reedy sound of the English horn—as agile as an oboe but less nasal, and as clear as a flute but more thoughtful. It is also there that I fell head over heels for the French horn, that quirky coil of tubing muted by the player’s hand, but which still manages to sound as if the gods are calling to us mere mortals from a mountain top.

I watched the cellos in a pizzicato sprint chased by basses, and waited eagerly as the timpani player roused himself from apparent slumber (or was it just boredom at being left out for 64 bars?) to release a round of growing thunder. And I loved the horn section—the silken, golden brass sent me soaring—and the strings in full throat, with that wondrous luster of resonating wood that expands the heart.

The flutes could be sublime, but I would get restless when, as seems to be a universal affliction among flautists, their pitch was sharp. It made the pure tones shrill, and the budding arranger in me would have preferred to give their parts to the English horns, who I knew would do them justice.

It is also at the opera, in that same seat on the first row, that I learned the rules of concert etiquette. Generally well mannered, even studious and proper, I was still a child. As such, on occasion I did things grownups frowned upon. Conductors, I discovered to my embarrassment, frown very deeply.

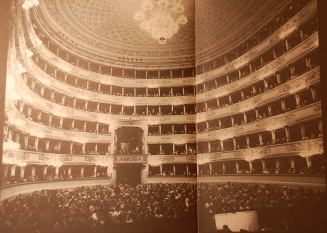

Il Teatro alla Scala, Milano, Italy, prior to World War 2.

| 9 Dimensions |

| Discography |

| Angst and Worship at the Opera |

| The Artists |

| The Producers |

| Holiday Letter |

| Contact |